Quotas promote gender equality

Canada’s 42nd federal election began in its usual fashion. Pundits decried the cost to taxpayers. The phrase “middle-class values” was overused. Partisans immediately began thinking of clever hashtags.

In other news, only 30 per cent of the major parties’ candidates are women. The percentage of female candidates currently sits below 2013 levels, when it was still a dismal 31 per cent. During the last federal election, this translated to 72 seats in the House of Commons — or about a quarter of all MPs.

This is poor representation. 50 per cent of the people living and voting in Canada are women, and we deserve to be represented in all levels of government.

But in order for this to happen, Canadians must have the opportunity to vote for women. That doesn’t mean having one token woman on the ballot. We need multiple women from different political parties across many constituencies.

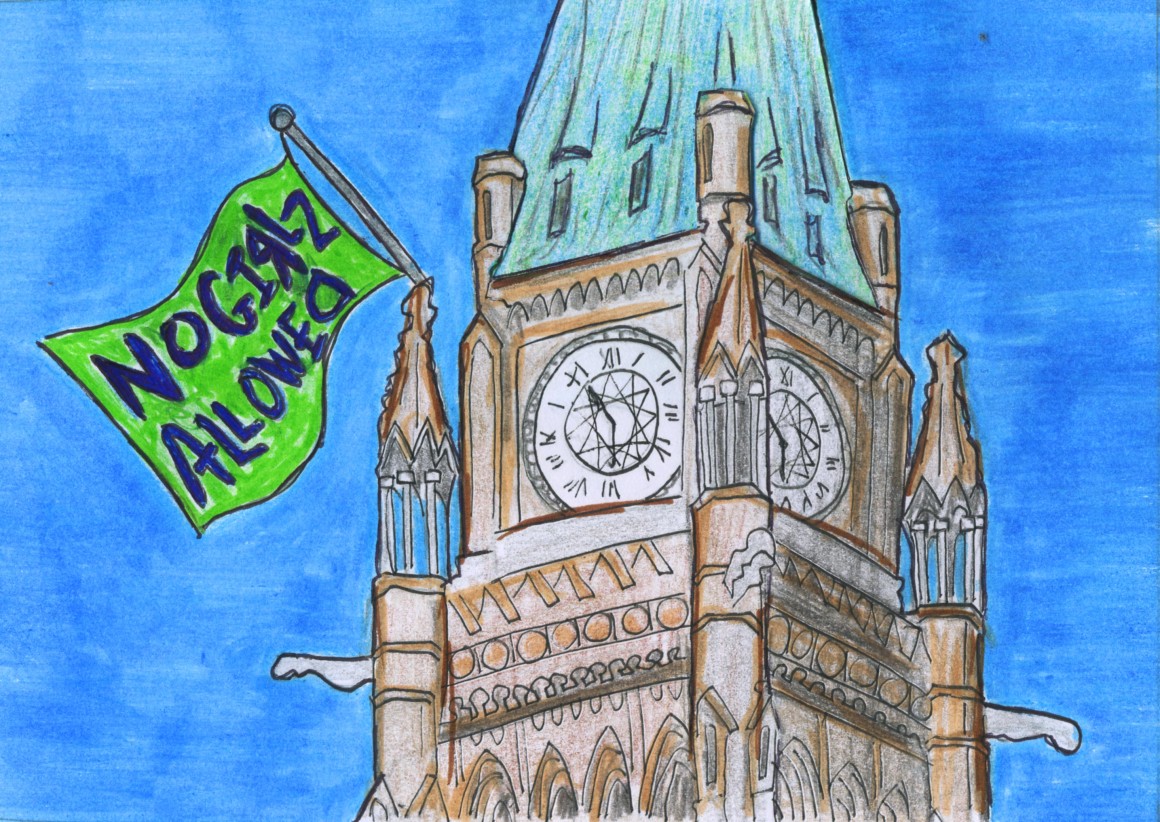

Which is why Canada’s political parties need a voluntary party quota. This quota would mandate both that parties nominate a certain percentage of women, and that they run women in ridings where the party has a chance of winning.

Opponents of quota systems claim that women shouldn’t be elected to public office just because they’re women, and that quotas discriminate against men.

It’s true that women shouldn’t hold political office just because they are women. But simply allowing women to run for public office isn’t enough to adequately involve women in the political process.

Equality doesn’t materialize when formal barriers are removed. Discrimination, casual sexism and hidden barriers prevent women from being selected as political candidates.

It doesn’t matter if everyone has the same equal opportunities if women continue to be systematically discriminated against. Until the results of a system are equal, equality doesn’t exist in a meaningful way. Quota systems are a way to compensate for these hidden barriers.

Two of Canada’s political parties have already done this. In 1993, the Liberals set a target where 25 per cent of their elected caucus should consist of women. The NDP adopted a target of 50 per cent female candidates in 1985, and also enforce a rule that at least one woman must be in the running at the nomination stage.

Compared to Canada’s other major political parties, these quotas are working. 41 per cent of NDP candidates in the upcoming federal election are female. Although it’s still short of their party-mandated quota, it’s higher than other political parties. The Liberals have 33 per cent female candidates, while the Conservative Party trails with 20 per cent.

Voluntary party quotas won’t solve all of the issues faced by women participating in politics. But they make the nomination process more transparent and formalized for everyone — including men. Quotas also help ensure there is more than one woman on committees or in meetings, eliminating the pressure faced by token women.

Stephen Harper has appointed more women to the cabinet than any other prime minister. The NDP consistently run the highest percentage of female candidates. And both of these parties are trading the lead in the polls. Canada’s political parties have shown that women are more than capable leaders — when they’re elected.

Research has shown that Canadians don’t discriminate against women at the ballot box. The reason people don’t vote for women is because the opportunity to do so doesn’t exist.

Political parties exercise a lot of control over nominations. They have a responsibility to seek out women and prioritize our involvement in politics.

Kate Jacobson

Gauntlet Editorial Board